[ad_1]

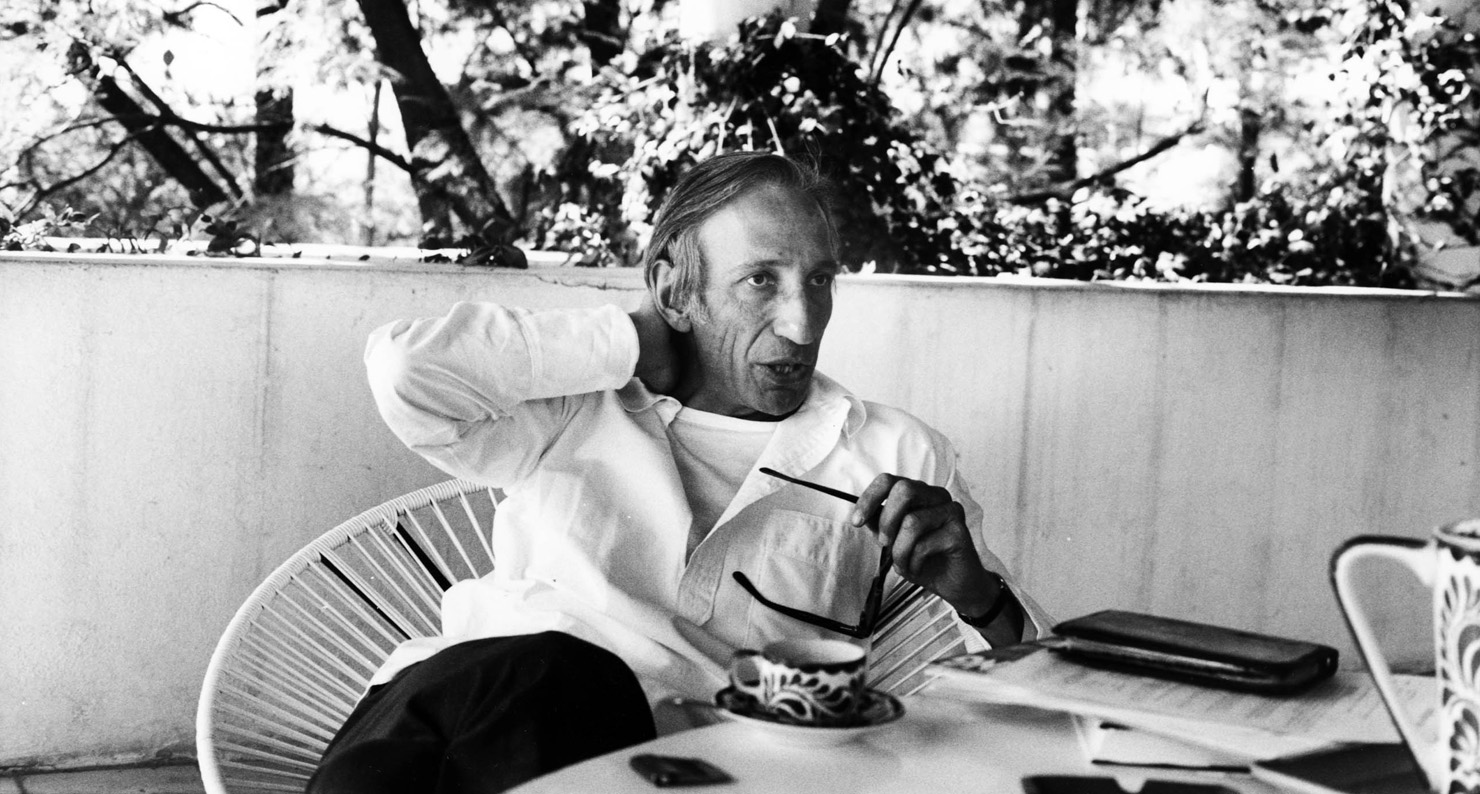

Published in 1971, this radically subversive and profound book is a spectacularly cerebral exposition on the failings of schools and offers a critical discourse on institutionalized education in modern economies.

The book is radical, disputed, subversive, intellectual, and a marvelous feat in every sense.

The first chapter, Why We Must Disestablish School is a scathing indictment of traditional educational institutions that seek to uphold and promote the status quo and convince the public that we need the society as it is today: “Many students, especially those who are poor, intuitively know what the schools do for them.

They school them to confuse process and substance. Once these become blurred, a new logic is assumed: the more treatment there is, the better are the results; or, escalation leads to success.

The pupil is thereby “schooled” to confuse teaching with learning, grade advancement with education, a diploma with competence, and fluency with the ability to say something new.

His imagination is “schooled” to accept service in place of value.

Medical treatment is mistaken for health care, social work for the improvement of community life, police protection for safety, military poise for national security, the rat race for productive work.

Health, learning, dignity, independence, and creative endeavor are defined as little more than the performance of the institutions which claim to serve these ends, and their improvement is made to depend on allocating more resources to the management of hospitals, schools, and other agencies in question.”

One of the facets he emphasizes is that when you attempt to organize education from a top-down bureaucracy, managed by authoritarian teachers, organized into standardizing logic of curricula, sanctified by abstract diplomas and certification, and strictly confined by age, the results and long term consequences are less than spectacular.

Illich’s counter-proposal, in short, is open-learning based on peer-to-peer networking (remarkably predicting of a world where people are linked via computers years and years before personal computing and the internet came into existence) and the disestablishment of degrees and certification as worldly qualifications.

Illich’s most direct criticism is the idea that formal education solves problems.

Rather than being about skill acquisition or personal development, Illich identifies schools as the ideological wing of the consumption-production engine that is capitalism.

The role of schools is to produce ignorance rather than insight, to create credentials and envy of credentials rather than mastery, to suck up surplus labor and intellect in the Promethean furnace of a culture consuming itself.

The criticism starts with Dewey’s ideas about education and moves through Johnson’s Great Society, international development, drawing heavily on Illich’s personal experiences in Mexico, the Vietnam War, and the industrial design of the transistor radio.

Don’t mistake this for Marxism though; Illich calls out the Soviet system as another gear in the world-spanning educational system.

Against traditional classrooms and curriculum, Illich imagines ‘learning webs’, where computers would connect people who wanted to learn something to people who already knew it, forming tutoring pairings and affinity groups that meet in cafes and converted shopfronts.

Mass production of tapes and audiobooks, along with appropriate technology in the developing world, will liberate minds.

Most of Illich’s criticisms are directed at the liberal mainstream perspective on education, and he’s not afraid of citing Milton Friedman’s otherization of school systems as a positive example, but mostly it’s the idea of any sort of formal, obligatory, schooling that is the enemy.

There’s a direct line between military discipline and educational discipline, and for Illich, both are wasteful, anti-human, and evil. The institutional attempt to achieve a goal will always fulfill its opposite.

As a historical artifact, this work was published in 1971, when for a brief glorious moment it seemed like the Counterculture would triumph, and that all the corrupt and evil institutions of a rotten society would crumble to be replaced by new dawn met people where they were.

Now, more than 40 years on, we know that this moment would last only a little longer. But Illich, even in his strident utopianism, wasn’t wrong.

Speaking as someone in the 23rd grade, too much education is useless credentialism that serves to indebt the ambitious working classes.

Those with power and money have their own networks of private tutors to pursue actually effective education for their children, while basic skills like knowing how to do something, or how to think in a straight line for 500 words, are increasingly the privilege of the elite.

Deschooling society is dated in the context of our current systems but it still presents novel conceptions of what a de-schooled society would look like.

It does critique the core tenets and assumptions of the modern education system rather ruthlessly and offers a vision of alternatives.

A few insightful quotes from the book:

“School is the advertising agency which makes you believe that you need the society as it is.”

“Most learning is not the result of instruction. It is rather the result of unhampered participation in a meaningful setting. Most people learn best by being “with it,” yet school makes them identify their personal, cognitive growth with elaborate planning and manipulation.”

“School has become the world religion of a modernized proletariat, and makes futile promises of salvation to the poor of the technological age.”

“Schools are designed on the assumption that there is a secret to everything in life; that the quality of life depends on knowing that secret; that secrets can be known only in orderly successions; and that only teachers can properly reveal these secrets.

An individual with a schooled mind conceives of the world as a pyramid of classified packages accessible only to those who carry the proper tags.”

“The machine-like behavior of people chained to electronics constitutes a degradation of their well-being and of their dignity which, for most people, in the long run, becomes intolerable.

Observations of the sickening effect of programmed environments show that people in them become indolent, impotent, narcissistic, and apolitical. The political process breaks down because people cease to be able to govern themselves; they demand to be managed.”

“Man must choose whether to be rich in things or in the freedom to use them.”

“School prepares people for the alienating institutionalization of life, by teaching the necessity of being taught. Once this lesson is learned, people loose their incentive to develop independently; they no longer find it attractive to relate to each other, and the surprises that life offers when it is not predetermined by institutional definition are closed.”

“The American university has become the final stage of the most all-encompassing initiation rite the world has ever known.

No society in history has been able to survive without ritual or myth, but ours is the first which has needed such a dull, protracted, destructive, and expensive initiation into its myth.

The contemporary world civilization is also the first one that has found it necessary to rationalize its fundamental initiation ritual in the name of education.

We cannot begin a reform of education unless we first understand that neither individual learning nor social equality can be enhanced by the ritual of schooling.

We cannot go beyond the consumer society unless we first understand that obligatory public schools inevitably reproduce such a society, no matter what is taught in them.”

“A second major illusion on which the school system rests is that most learning is the result of teaching. Teaching, it is true, may contribute to certain kinds of learning under certain circumstances.

But most people acquire most of their knowledge outside school, and in school only insofar as school, in a few rich countries, has become their place of confinement during an increasing part of their lives.”

Also Read:

[ad_2]

Source link